Females of some Asian salamanders of the genus Hynobius deposit in streams their eggs embedded in a translucent envelope called an ‘egg sac’. The edges of the envelope exhibit a spectacular blue-to-yellow iridescent glow, which instantaneously disappears when the sac is removed from water. Combining optical measurements, microscopy and mathematical modelling, we report in the journal Soft Matter that (i) the Hida salamander egg sac wall is a 3D structure with a periodic 1D modulation causing iridescence, and (ii) removal of the egg sac from water causes a shift of the backscattered light to the UV range due to the exchange of surrounding mediums (from water to air) with very different refractive indices, hence, resulting in the loss of iridescence in the visible range. Further analyses are required to identify whether the structural colour and/or iridescence might attract male salamanders for external fertilisation, constitute a visual signal to avoid cannibalism, or are mere by-products of egg sac material internal structure selected during evolution for its mechanical properties.

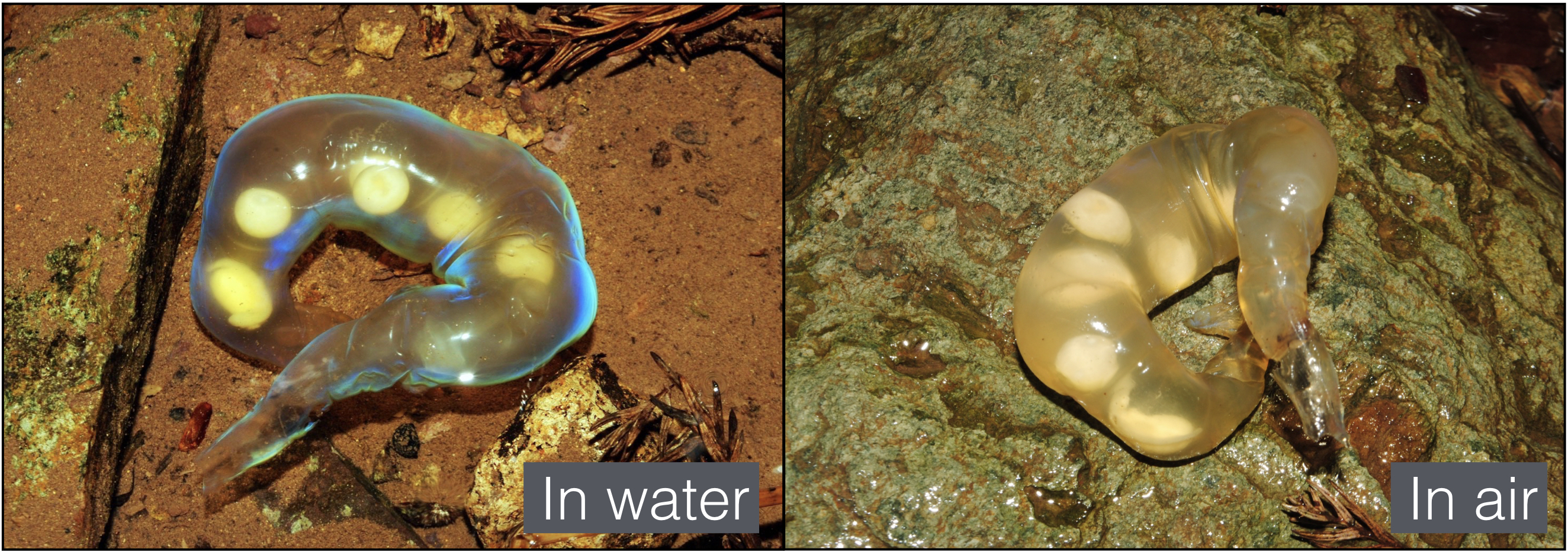

Here, we study an iridescence phenomenon occurring in the egg sacs of Asian salamanders of the family Hynobiidae; the eggs of these amphibians are laid embedded in elongated sacs of jelly-like material, then externally fertilized. In various species, egg sacs are iridescent in water but they immediately and completely loose this property when they are removed out of water (Fig. 1).

First, we present in our article the structural basis and physical principles explaining the observed blue to yellow iridescence of Hynobius kimurae egg sacs. Using SEM (scanning electron microscopy), we observed the presence of a potential diffraction grating (thin fibres of 190 nm length scale) on the inner surface of the envelope. We then performed TEM (transmission electron microscopy) imaging of cross-sections of the envelope parallel or perpendicular to the elongated axis of the egg sac and show the existence of quasi-periodical structural variation (fibres) of the material across the bulk of the egg sac envelope. Fourier-power analyses of FIB-SEM (focused-ion-beam scanning electron microscopy; Movie 1) data then indicated the presence, in the bulk of the envelope, of a photonic structure with a quasi-periodic 1D modulation of 140 to 190 nm. Taking into account an approximate 18% shrinkage due to the preparation of samples for electron microscopy, this translates to a period of 170 to 230 nm in the fresh egg sac. As discussed in the supplementary material, this period seems also to vary depending on the localisation on the crescent-shape egg sac: smaller length scale on the outer curvature and larger length scale on the inner curvature. This trend is compatible with a mechanical origin of this variation because the periodicity is running parallel to the axis of the egg sac.

As the iridescence is present mostly on the sides of the envelope, i.e., at high incident illumination/observation angles, we expected the effect not to be specular. We tested this hypothesis by shining a light source and observing the variation of the optical response of the egg sac when changing the position of the sample or changing the orientation of the observer (camera). Both experiments indicate that constructive interference leading to structural colours is only observed in backscattering. These results rule out the possibility that the iridescence is due to a thin film or a multilayer. Additionally, our spectroscopic measurements confirm that the iridescence appears along the radius of the egg sac (while it is absent along the elongated axis) and is due to backscattering.

Next, we applied a Fourier-power analysis to our FIB-SEM data and showed that the predicted iridescence generated by these simulations matches the experimental photographic/spectroscopic data. Indeed, the Fourier-power modelling correctly predicts that (i) iridescence of the egg sac submerged in water spans the blue-to-yellow visible range of the light spectrum and (ii) the iridescence experiences a blue shift of about 90 nm (making it appear mostly in the UV) when the egg sac is removed out of the water. This spectral shift, hence loss of visible iridescence, is due to a larger difference in refraction index between the air/egg-envelope versus water/egg-envelope interfaces. Note that the diffuse yellow hue of the egg sac in air is likely due to the absorption or scattering of blue wavelengths inside the material.

Finally, we have provided several hypotheses for the potential biological function of the observed iridescence (recognition of egg sacs by males for external fertilisation or display against predators or against intra-specific cannibalism), although we emphasize the possibility that iridescence is a non-functional by-product of the structural features of the egg sac envelope selected for their mechanical or anti-microbial properties.

We note here the difficulties associated with the analysis of optical responses of soft materials because they tend to exhibit poor conservation properties (the material can alter with time) and their structural and photonic properties are easily perturbed during experimental procedures such as fixation and preparation for electron microscopy.

Figure 1 - Photograph of a Hynobius kimurae egg sac in water and outside of water.

Figure 1 - Photograph of a Hynobius kimurae egg sac in water and outside of water.

Movie 1 - FIB SEM reconstructions of XY, YZ and XZ planes of the egg sac material. The stacking direction is along the Z-axis.

For additional informations, please download the original article here:

Translucent in air and iridescent in water:structural analysis of a salamander egg sac

Zabuga, Arrigo, Teyssier, Mouchet, Nishikawa, Matsui, Vences & Milinkovitch

Soft Matter (2020) 16, 1714-1721, DOI: 10.1039/c9sm02151e

This research was performed in collaboration with:

- Jérémie Teyssier from the Department of Quantum Matter Physics, University of Geneva, Switzerland

- Miguel Vences from the Zoological Institute, Braunschweig University of Technology, Germany

- Kanto Nishikawa and Masafumi Matsui from the Graduate School of Human and Environmental Studies, Kyoto University, Japan

- Sébastien Mouchet from the Department of Physics, University of Namur, Belgium.